This is the first of a two-part series exploring the Nordic mining equipment sector; an industry grounded in complex engineering and tested by shifting market cycles, geopolitical friction, and regulatory hurdles. In part 1, we map out the mining equipment value chain and the relevant demand drivers (incl. commodities, miner capex, permitting, etc.). Part 2 will build on this by benchmarking the Nordic OEMs, assessing their competitive positioning, and relative attractiveness.

This is a highly complex industry with many moving pieces, and we do not pretend to hold the perfect answer. We welcome perspectives to sharpen our thinking further.

The mining OEM value chain and market dynamics

The Nordics are home to some of the world’s leading mining equipment manufacturers, a position rooted in the region’s long and rich mining heritage — with Sweden as an early anchor point. Some even joke that the world’s first joint-stock company was founded at the copper mountain in Falun, Sweden, in the late 1200s. By the 1600s, the Falun Mine was producing ~2/3 of the world’s copper and later added gold before operations paused in 1992. Remarkably, after a 30-year sabbatical, the 1,000-year-old minefield was revived by Alicanto Minerals in 2023 and is still in operation today.

Nordic OEMs are still benefitting from that proto-industrial head start, with Epiroc (OM: EPI A) and Sandvik (OM:SAND) dominating upstream operations, and Mesto (HLSE:METSO) and FLSmidth (CPSE:FLS) dominating the mid-downstream flow sheet.

Upstream

The upstream segment of mining covers exploration, development, and extraction; the stages where the resource potential is identified, evaluated, and excavated. During this stage, operators are carefully considering what mining method is most suitable for the site and how the flow sheet is best put together — which subsequently impacts what OEM provider is better positioned. After all, it is a long (+25yrs) and costly process to set up a mine — and once set up, it can difficult to retrofit.

The most common type of mining is surface mining (57% of mines) — also referred to as open-pit mining — whereby material is removed in layers from the surface of the earth. The less common (but growing) method is underground mining (43%) which is used when the resources are buried so deeply into the ground that extracting via open-pit is not economically feasible.

While Epiroc and Sandvik are key players, they face significant competition from the likes of Caterpillar (NYSE:CAT) and Komatsu (TYO:6301) in surface-mining projects — specifically for load and haulage. However, when it comes to drilling and the wider underground mining process, which demand more complex technology, Epiroc and Sandvik controls ~80% of the market.

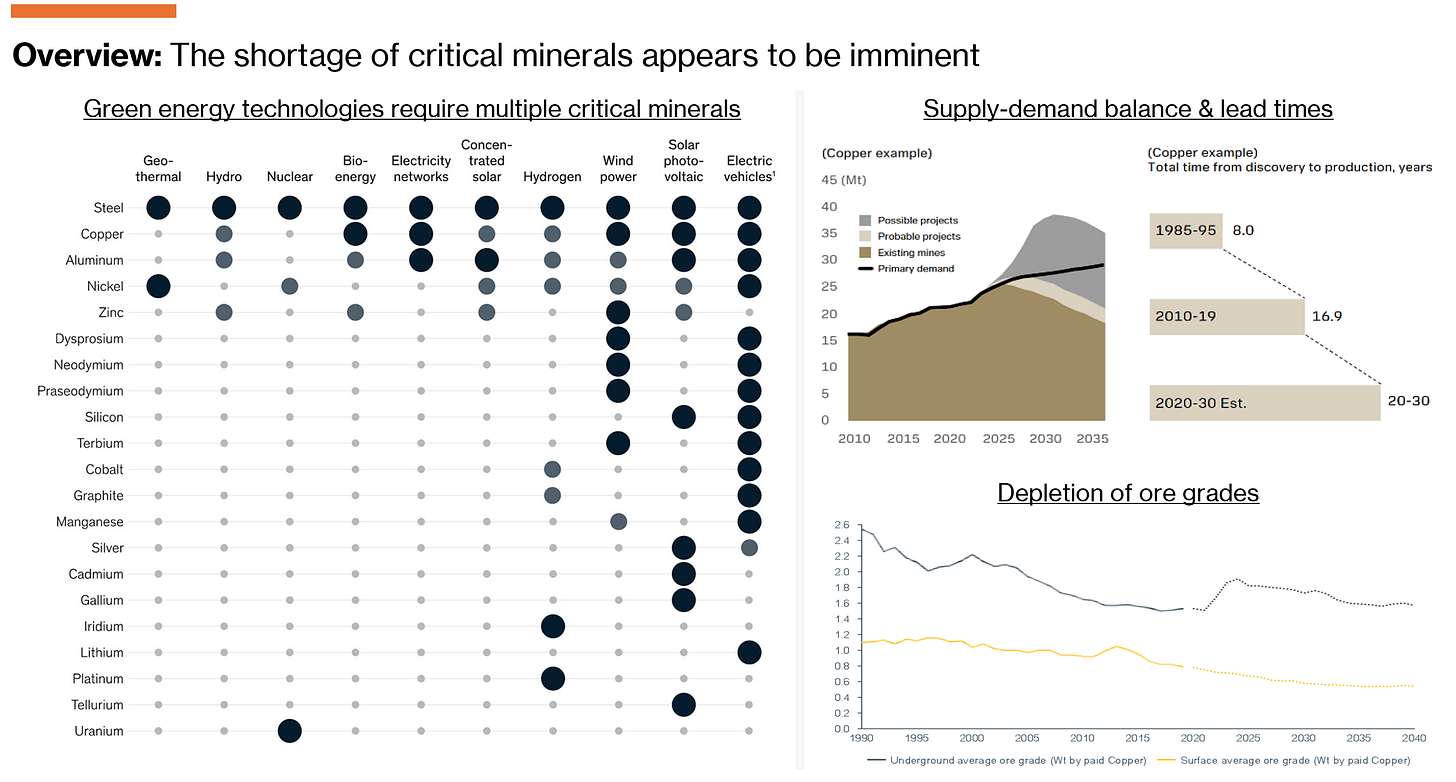

As ore grades are declining (down ~50% L25Y), consensus is that underground mining projects will gain share. Given the cost per metric ton is generally higher for underground mining vis-á-vis open-pit, there is a clear incentive for mining OEMs to find avenues to offset said cost for operators. This is done by, inter alia, electrification of equipment. An electrified fleet enables operators to cut OPEX on ventilation — needed to for harmful gasses from diesel motors, etc. — which can account for up to 40% of total OPEX for an underground mine. The total cost of ownership (TCO), a key purchasing criteria for operators, is estimated to be 15-20% lower with an electrified fleet — after accounting for the premium charged from such equipment.

Both Epiroc and Sandvik stress that this is not only an opportunity in the context of new equipment sales — the electrified solutions also create stronger lock-in and thus higher capture rates for future aftermarket sales. This is in part due to the solutions being governed by service agreements (e.g., multi-year maintenance contracts), but also due to the technical expertise needed to service such equipment. In a similar vein, automation and software solutions are increasingly bundled into offerings to add operational entrenchment and drive recurring revenue streams for OEMs.

Granted, for “higher-tech” equipment sales to materialize — regardless of the financial rationale — it requires convincing a highly conservative industry with aversion to change. Before that, though, more greenfield mining projects must come online, which has been impacted by, i.a., push-back on new mining permits. In fact, the average permitting phase has gone from 6-7 years in the 1990’s to 12-14 years in the 2000s.

Mid-downstream

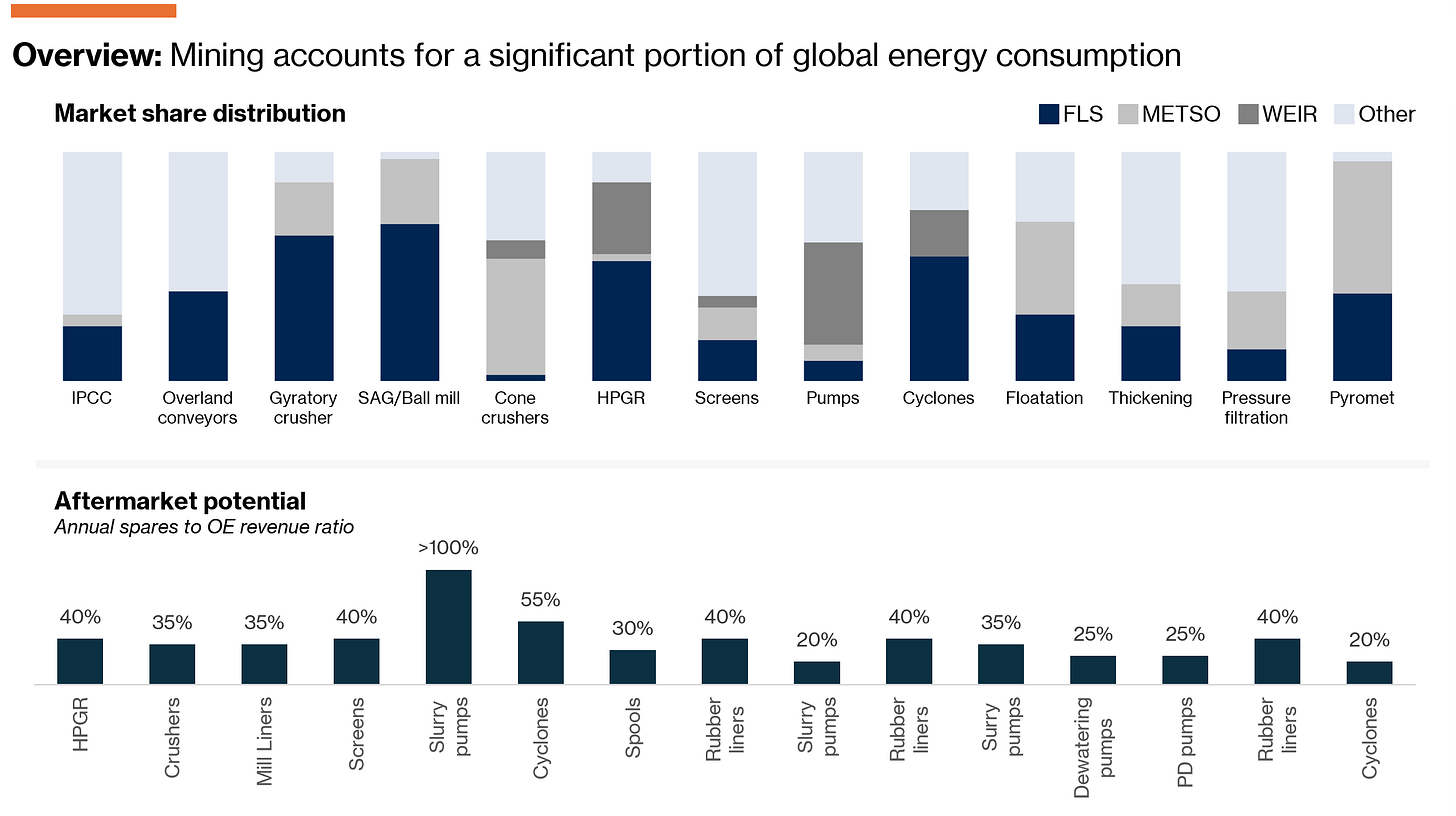

While upstream mining is about access, the mid-to-downstream segment is about conversion; turning extracted material into saleable output. Once ore is brought to the surface, it enters a tightly sequenced series of heavy-duty equipment combining brute force, flow-control, chemical processing, and precision engineering. Each stage is both capital and energy-intensive, with equipment performance and throughput directly impacting plant economics. In fact, mining and mineral processing is estimated to account for ~6% of global energy consumption, with the grinding process alone making up ~2.4%.

As such, there is significant opportunity for mining OEMs to improve the emissions profile of equipment — essentially maximizing yield for each unit of energy consumed. One example is the shift from conventional SAG/ball mills toward high-pressure grinding rolls (HPGRs), which can deliver 15-30% lower specific energy consumption. The same TCO logic applies; the equipment is sold at a higher upfront cost (~20%), which is fully offset by the lower OPEX through improved efficiency.

It is worth noting that equipment in this portion of the value chain is, on balance, less technologically advanced and in some cases more commoditized (e.g., buckets, feeders, and screens). Consequently, competition is more fragmented in select categories, with local mom&pop-shops and low-cost Chinese OEMs compressing aftermarket capture rates — ultimately squeezing the margin potential.

For mid-to-downstream operators, declining ore grades mean that larger volumes of input must be processed to yield the same quantity of output. This creates a two-fold dynamic: (i) the value proposition of efficiency gains in new equipment rises, as operators look to offset higher unit costs through improved energy and throughput performance; (ii) higher volumes intensify wear and tear on the installed base, expanding the aftermarket opportunity through parts, maintenance, and service contracts. Worth noting that some of the longer-term upside may be tempered by the relative shift toward underground mining, where lower throughput rates per mine constrain the total volumes processed.

On the topic of aftermarket sales — an industry buzzword often used to separate the non-cyclical from the cyclical — it is worth double-clicking on the quality and resiliency of these revenue streams. OEMs exercise considerable discretion in how they classify aftermarket activity (e.g., retrofitting vs. spare parts vs. consumables, etc.), which makes strict apples-to-apples comparisons challenging. We will expand on this in Part 2.

Leading indicators of future mining OEM demand

Demand for mining equipment is shaped by a broad set of factors, including commodity price levels, fleet age, ore quality, the regulatory environment, and financing conditions. Ultimately, these variables define miners’ incentives to deploy capital toward exploration campaigns and new mine development.

Commodity prices

The world’s growing demand for critical minerals — copper, lithium, zinc, nickel, etc. — far outstrips the supply. Couple this with ever-longer lead times and permitting delays, and you are left with a structurally skewed supply-demand balance that will take decade(s) to revert. For context, the world would need ~300 new mines by 2030 to bridge the battery-minerals supply gap alone.

The underlying secular drivers are well understood, but for completeness, here are some of the common themes: (i) Growing population, expanding middle class, and rapid urbanization; (ii) Green transition and electrification push, spanning EVs, renewables, and modernized power grids; (iii) Datacenters and AI infrastructure, and latest (iv) defense spending.

These forces anchor a long-term pull on minerals — and commodity prices are already reflecting the constrained supply. This price strength tends to shape miners’ investment appetite; a point further elaborated in the next section.

That said, miners’ own initiatives also play into the run-up in commodity prices. This is because mining companies were so hurt badly during the GFC (‘08-’09) and subsequent overcapacity amid the slowdown in Chinese construction (‘12-’16). Since then, they have been far more cautious about the volumes they bring to online. As Glencore’s CEO Gary Nagle puts it, the market needs to be “screaming” for the metal [copper] before new production will commence.

In the context of Nordic OEMs, it is helpful to understand their exposure across commodities. Generally, the more exposure toward scarcer resources (e.g., copper, gold, battery metals) versus sufficiently supplied resources (e.g., iron ore, platinum). Another helpful layer is the production intensity (and equipment) required to produce a unit of resource. To that end, both copper and gold is tough to mine and requires specialized equipment, whereas iron ore and coal is more straightforward.

With the current outlook, it is highly likely that all four names will increase their proportionate exposure toward copper, gold, and battery minerals.

Aging fleet, declining ore grades, and miner capex

As miners have tightened capital spending, they have prioritized sweating the existing asset base rather than expanding capacity. This restraint has supported mining OEMs through resilient, higher-margin aftermarket sales but has also created an underinvested asset base to handle any added capacity.

I am 71 years of age, fat, bald, past my prime… that is what the copper mines look like around the world - Rick Rule

At Caterpillar’s 2022 CMD, the global average mining machine age was cited at 11.7 years, while Epiroc reports 8.4 years for its installed base. We expect 8-10 years to be true for most Nordic OEMs. Combined with declining ore grades — which will require ~30% more material to be processed to maintain current output by 2030 — we would expect that aftermarket demand will remain elevated, while fleet renewal and new mining projects will gradually lift new equipment orders (i.e. we do not expect a sudden uptick in greenfield equipment orders).

As noted earlier, miners’ incentive to invest is closely tied to the commodity price. Tracking the miners’ capex guidance can provide some read-across to anticipated OEM orders. The capex spend is often categorized as being (i) sustaining/maintenance capex; (ii) expansion capex; (iii) exploration/evaluation capex; and (iv) decarbonization capex. Today, roughly 50% of total capex falls into sustaining/maintenance capex, wheras 10 years ago, 80% went into expansion capex.

While difficult to forecast with conviction, consensus (which is grounded in miners’ guided capex budgets) suggests that mining capex will remain elevated N3Y, though YoY growth is expected to decelerate to LSD. In real terms, mining capex still sits ~40% below its 2012 peak. Ultimately though, the ability to deploy capital also depends on the pace (and success) of the permitting process.

Permits, geopolitics, and tariffs

Prolonged permitting has all else equal held back capex spend and consequently output volumes. The widely debated Big Beautiful Bill actually provides some positive read-across both with regards to permitting — but also in the context of obtaining financing, which has been another constraining factor for junior miners in particular.

Permitting: “An environmental assessment for which a fee was paid under this section shall be completed by not later than 6 months… [and] an environmental impact statement… shall be completed by not later than 1 year” (p. 619-620)

Financing: $500,000,000 to the ‘Department of Defense Credit Program Account’ to carry out… loans, loan guarantees, and technical assistance… for the development of reliable sources of critical minerals” (p. 673)

Domestic production: $2,500,000,000 for additional activities to improve the United States production of critical minerals through the National Defense Stockpile (p. 672)

While difficult to triangulate the exact impact of this, it nonetheless pairs well with the pro-American narrative from the Trump administration. As such, we argue it is sensible to expect a forward-leaning stance on general permitting matters. Granted, there are constraints as to how self-sufficient (and how fast) the U.S. can be in this domain — latest exemplified by its rare earths agreement with China. If anything, the realization of this dependency should further incentivize the administration’s desire to allow for more mining activity.

The U.S. is only part of the puzzle though. Several other countries — especially in the LATAM region for copper — are instrumental for future mining activity. Similarly, on the demand side, China remains the largest consumer of copper (~55% of global production). While other countries’ share are poised to grow (e.g., India modernization, U.S. infra, etc.), there is a certain degree of risk tied to Chinese demand.

The ongoing tariff drama has done little to build near-term conviction. Miners’ capex decisions rely not only on positive commodity fundamentals but also on a relatively predictable regulatory environment and a stable macroeconomic backdrop. As such, we would expect larger-scale investments to be deferred until there is greater clarity.

For Nordic OEMs, the direct and indirect effects are yet to be seen. All companies have been fairly consistent in that they can protect margins via re-routing supply chains, etc. All this — along with a detailed benchmarking of the Nordic OEM landscape, incl. our views on relative attractiveness — will be elaborated further in Part 2.

Saw your comment on the rare earth mining post by Boredom Baron. Is there a technology on the horizon that will allow this in an efficient and environmentally neutral manner ?

Excellent article and deep dive to this topic. Based on my experience working with these companies over the past few year, I would add one important topic - digital services and solutions. Most of these companies are currently developing their own digital offering. Especially now when different AI capabilities are becoming more mainstream and functional. This gives them multiple benefits, saving on costs by making the equipment run more efficiently, saving on maintenance costs (for the customer) by introducing services like condition based, predictive and prescriptive maintenance, but most importantly by giving the equipment manufacturers additional, recurring revenues, helping to even out the cycles in the industry.

Some of these companies have already poured millions in their own development of these solutions whereas I see this should be treated more like a traditional make-or-buy decision - buying existing, cutting-edge software platforms from the market and concentrating their own work on areas where they have their unique competencies and strengths i.e. knowing how the equipment runs and how the mining processes work. This would radically fasten the time-to-market of these solutions, cut down development costs, and most importantly provide most value to the customers.

Looking forward to reading the second part of the article.